Urban planning is a lineage problem. Well, to be completely honest, at Solidatus, we’re convinced that all manner of things are lineage problems.

What does this have to do with data management? Well, bear with us, as the parallels we explore at the start of this blog post – the third and penultimate part in our lineage series – will resonate with anyone planning to alter or enhance their data estate in any way.

Before we dive in, if you need a primer on the concepts detailed in this article, be sure to read our guide to data lineage.

Let’s start by looking at an aerial view of two cities and their approach to their development. The first is Kolkata in India; the second is Shanghai in China.

Above: aerial view of Kolkata in India

Above: Shanghai in China before expansion (left); after expansion (right)

You can clearly see the differences in the planned expansion of the city. Kolkata has expanded into new territory and planned its road systems, fitting the various city zones around it, whereas Shanghai has just replaced the old with the new. SimCity, anyone?

It’s about the availability of resources – just like in SimCity, the urban planner has choices about what they can do – Do I have land? Do I have transport links? Do I have money? What’s most important? In both cases, there’s a river – a vital resource for most of the world’s great cities (New York has the Hudson, Rome has the Tiber, London the Thames, Paris the Seine…). So, building near to this really important asset is essential – nature is the best builder after all. Just as with the expansion of London to the south of the Thames, Kolkata had the option to expand into new territory on the opposite bank and could then plan for this. In the case of Shanghai, they clearly had built-up areas on both sides of their river, meaning a choice was needed on whether to bulldoze and replace. This is what they went with.

Why this is important

Is the project planned or under-planned? Note: very little is totally unplanned!

No one goes into any building project with no plan – they’re always building something. They can be qualified for this and have the right tools, they can consult others and try to make something that fits into the surrounding area’s plans – or they can just put up their building not knowing about utilities, the type of ground (Pisa, we’re looking at you) and hope for the best.

Let’s bring it a little closer to Solidatus’ UK HQ in London and the Thames.

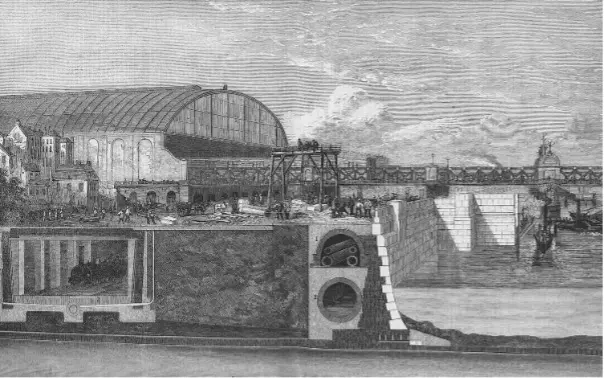

This river was once much wider than it is now (four times wider, as it happens), and when London needed to expand, it exploited this space, most recently to create room for underground tube lines and sewerage (both in the 1860s and again in the 2020s). Below are a couple of images giving you an idea of the construction projects where the cut-and-cover techniques were used to expand the Victoria Embankment, first for the removal of waste – thank you, Joseph Bazalgette – and then for the commuting public. We have a new(ish) road above it as a result, and the north side of the river is that bit bigger.

Above: historical view of the Victoria Embankment on London’s River Thames in the UK

Above: detail of historical cut-and-cover work on the Victoria Embankment

Above: further historical construction work in London

In the planned city, it’s easier to see how to add in utilities, and how to modify things to bring in new systems. One side of Kolkata will be easier to modernize than the other. Shanghai was built with a modern plan and these things in mind.

London certainly wasn’t built like this. It is a city built on a city built on a city approaching the end of its second millennium. That is why it is so expensive and increasingly impossible to add in new facilities, as the environment is so difficult to upgrade.

Cities as enterprises

Let’s bring this back to the ground and think of a large enterprise as a city. It has buildings, utilities, people etc… It has systems and controls, it has legacy and aspiration to modernize. Like London it has archaeology, and decisions made decades (or longer) ago have created the foundations upon which to build the new. Like London, it wants to be modern and be able to use the latest and greatest of everything. Fitting it all together is going to determine whether it will be a successful company that can trusted and governed, indeed whether it can even survive.

We can see how decisions such as the height and width of tunnels determine the dimensions of a London tube train.

So it is with the size of data centres, the choice of technology, and the network connections and locations in an enterprise.

Bringing it back to data

As we know, how we connect everything in an organization is most aptly modelled by lineage. This is best used in the first instance as a planning tool by providing an understanding of how elements are related and how they make the system work. This information helps inform decisions about the architecture, processes, and systems needed to support the data.

It also provides insight into what changes need to be made when new data sources, applications or utilities are introduced. Lineage can also be used to identify potential risks associated with data and ensure that it is managed in accordance with policies and regulations. Finally, lineage can help identify opportunities for optimization, such as reducing redundant processing or combining multiple data sources into a single source.

Putting lineage-centred planning into practice in the data office

Lineage can be used for planning in a variety of ways. First, it can provide an overview of the entire system and identify any weak points or errors in the process. By understanding the full scope of the system, organizations can better plan out their strategy and make decisions about which areas need improvement. Additionally, lineage can be used to track changes over time and identify trends that could be useful when making decisions about future projects or initiatives.

Lineage can be used for planning to help organizations understand how their data is being used by different stakeholders. By understanding where data comes from, who has access to it, and how it is being utilized, organizations can develop strategies that are tailored towards specific groups of users. This will help them identify potential opportunities for growth or areas where they need to focus more attention on improving their processes or systems.

Finally, lineage can also help organizations plan out their resources more effectively and conduct the sort of impact analysis necessary for any transformation project. By understanding where they come from and how they are being used throughout the organization, they can better allocate resources such as personnel or technology so that they are able to meet their goals more efficiently.

Insights for success

At its core, lineage provides us with a framework for understanding how certain events or ideas are connected to one another. This helps us see patterns in our life that may not be immediately obvious. For example, if you look at your family tree, you may notice that certain traits or interests run through generations. If you look at the history of an industry or field of study, you can identify key moments when certain innovations emerged and how they affected the development of that particular area.

By looking at lineage as a planning tool we can also gain insights into how different elements interact with each other in order to achieve success or failure. For instance, if we want to start a business, we need to consider all the factors involved such as market trends, customer preferences, competition etc., and then plan accordingly so that we maximize our chances of success. We can also use lineage to predict potential outcomes by looking at past successes or failures and using them as indicators for what might happen in the future.

Greenfield will always be easier, and if we plan with a lineage-first approach we’ll make a more sustainable environment. However, if we have legacy and stop to map it, then we can make the best of the situation we find ourselves in.

If Bazalgette were an enterprise architect, he might say: The principle in planning with lineage first was to divert the cause of the mischief to a locality where it can do no mischief.

The Happy CDO Project

We asked at the top of this article what this all has to do with data management, and lineage is a huge part of good data management. But it’s more than that. We think that lineage tools, better data management technology more generally, and methodology fit for the 2020s are central to being a happy CDO. These are core findings of proprietary research we recently commissioned, as discussed in a new white paper, Data Distress: Is the Data Office on the Brink of Breakdown? Part of The Happy CDO Project, we highlight in this research that 71% of the 300 senior data leaders in financial services in the US and UK that were surveyed have considered quitting their jobs as a result of a phenomenon that we define as ‘data distress’. This is just one of the findings that we explore – along with suggested remedies.