25 years on, what did the Barings Bank crash teach us?

Back in 1995, a young Futures Trader Nick Leeson was working in Singapore on arbitrage trading on the main Tokyo index – the Nikkei 250 – for Barings Bank when he fraudulently hid massive financial losses from the bank in both London and Singapore. The losses incurred by the 200-year-old bank were estimated at $1.3 billion in unauthorised trades.

“I’m sorry” – two words left on a note in his apartment was the only admission of wrongdoing on Leeson’s part. And on the face of it, the story was simple: a rogue trader extorts a bank for millions. His plan, like that of a James Bond villain, at the time was thought to be so ingenious that the senior management of the bank were powerless. And there was no way for Peter Norris, the Head of Barings Bank, to discover the fraud until it was too late. Norris later called Leeson ‘An Agent of Destruction’. Further investigations revealed that Norris probably overstated Leeson’s capabilities; as everything started with a simple entitlement error, and was followed by a systemic failure at the bank.

During his time at Barings, Leeson was promoted from bookkeeper to general manager and chief trader, whilst also being responsible for settling his own trades. These jobs are typically held by two different people; one running the back office and one running the front. But as Leeson was able to run both through an entitlement error, he had the capability to hide his losses from both his superiors in Singapore and London. There was no grand plan, nor was Leeson a hyper-intelligent villain. If you remove just one of the positions from Leeson then Barings Bank, in some form, would probably still be here today.

With access to both front and back-office systems, Leeson was actively defrauding the bank. He had already accrued huge losses when he decided to sell TOPIX volatility, which then imploded with the Kobe earthquake, creating financial losses that the bank could not recover from. All his losses were funnelled through the infamous ‘five 8s’ account, while at the same time he managed to falsify profits back to London. Despite suspecting something was seriously wrong, London ultimately fell prey to Leeson’s inflated profit claims which leaves us to wonder: why did they keep advancing Leeson more money when the settlements were so low?

There is a famous phrase that states ‘In the Land of the Blind, the One-Eyed Man is King’ and this is probably the best analogy I can give. The senior managers were blinded by profits and did not understand the complexities of the markets and details of the trades, giving Leeson a place to hide his growing losses. To everyone’s amazement, Leeson was the only one who understood how the system worked and, ultimately, how to move data to exploit it.

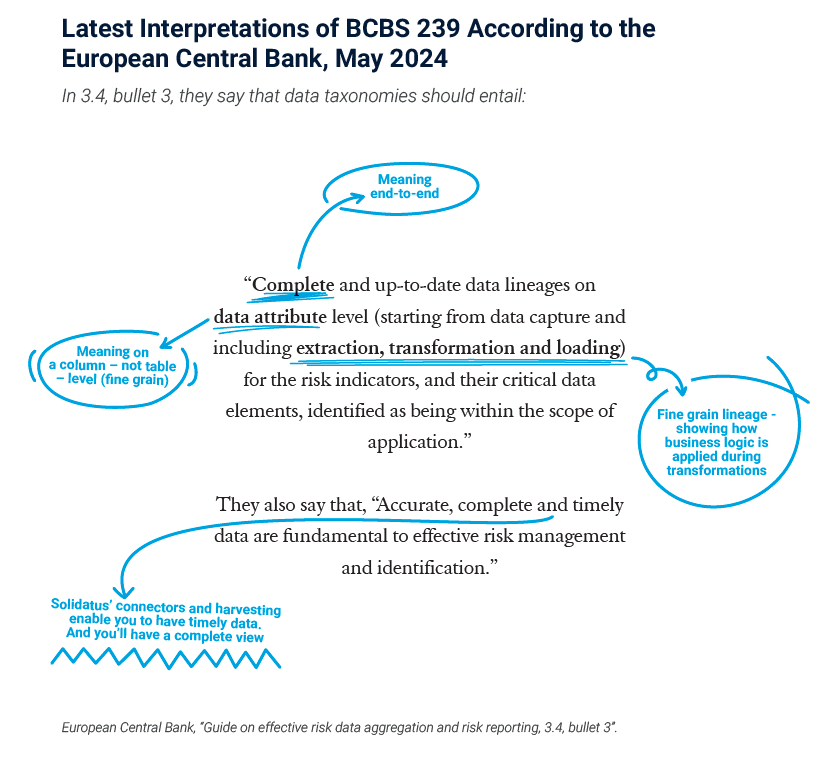

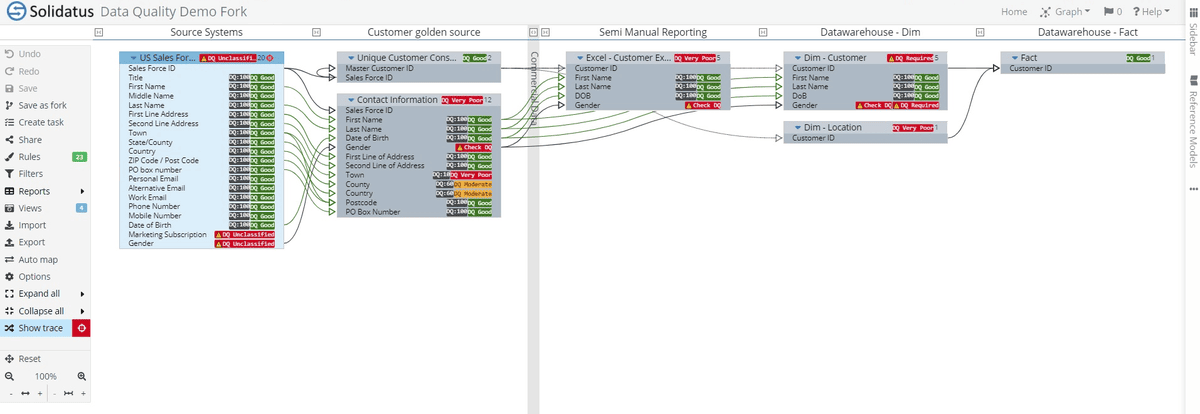

When looking at banking data lineage now, we can appreciate how difficult it is to track a single thread of data through the data landscape without a solution like Solidatus. What would Barings have given to visualise how the data moved through their organisation, and with additional data quality scoring, tracking data anomalies up and down stream would have high-lighted Leeson’s hidden account.

The Solidatus Solution

Think of a large international bank. Let’s say they have 20,000 traders and back-office staff across the world, each of those individuals have access to hundreds of systems and hundreds of thousands of data points. With hundreds of organisational changes at a role and access level a day, just as it was back in 1995, this is an extremely complex and often manual process requiring an exacting focus from everyone involved in the process.

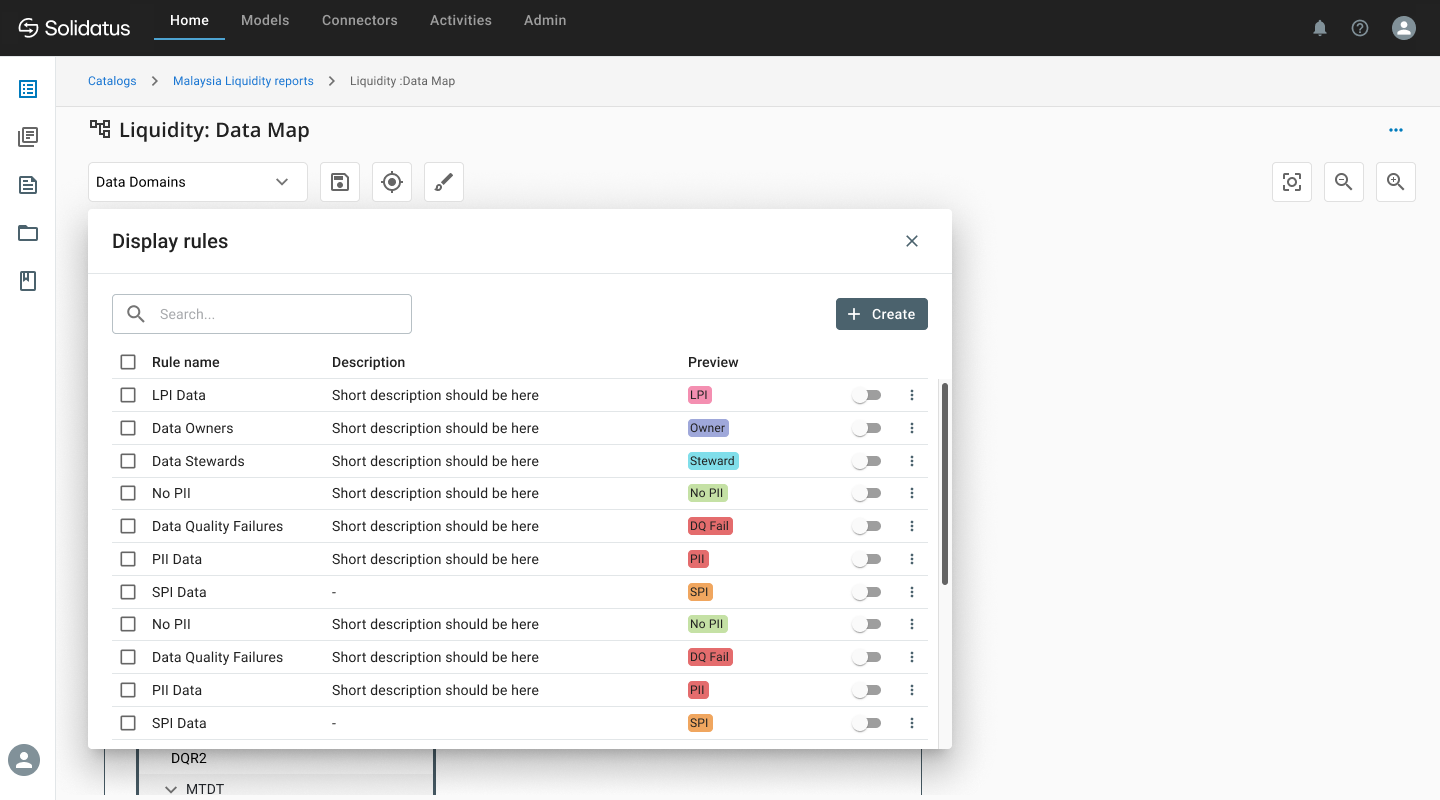

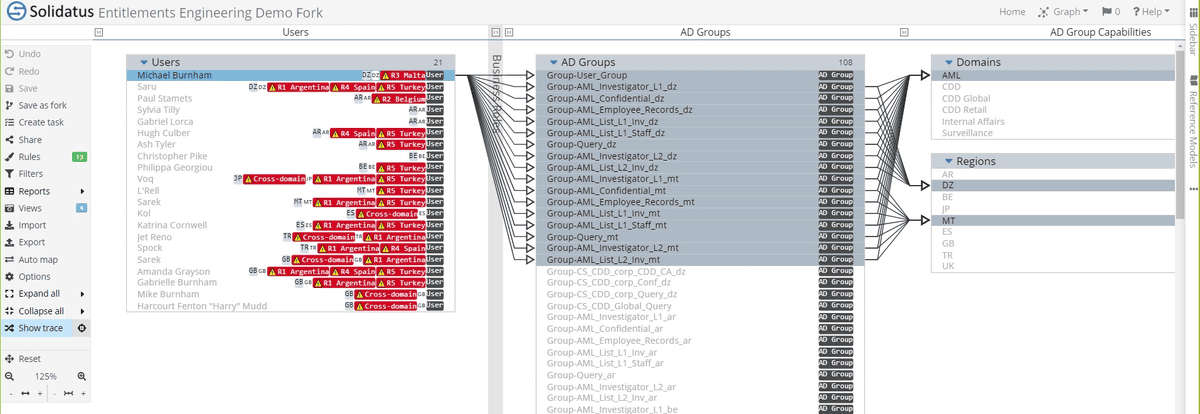

To understand the complexity of what a bank is facing, we have modelled an Entitlement Process in Solidatus. We imported users and their business roles from a HR system and associated them with the Active Directory (AD) Groups and AD Group capabilities. Business rales have been applied to confirm if individuals have appropriate access to systems/data based on location, function or role.

Entitlement Process:

Looking at the model, you can see where a user is based by the country code and the name, and country of employment. Selecting one user highlights their assigned AD Groups. Adding Rules to highlight access to multiple domains can also highlight toxic access rights combinations. When you can visualise the complexity of the Entitlement Process, it becomes obvious why the high risks of providing Leeson a toxic access rights combination at Barings was not appreciated.

Data Quality:

As we look back on the 25th anniversary of the Barings Bank collapse, if there is a lesson Leeson taught us, it is that complexity creates opportunity, both good and bad. Complexity devolves us of responsibility, creates shadows and dark places to hide data. So we have to ask ourselves, if we don’t understand the complexity of our data, are we creating a perfect storm for the next Nick Leeson?